Have you wondered where Vettel's performance in Melbourne fitted in the history of new car debuts in F1? Oh, alright then, well I have, and the reassuring news is: there have been cars with even bigger performance advantages in qualifying who have nonetheless failed to take world championships.

There follows a run-down of the best 15 performances* by brand new cars since the F1 world championship began in 1950. A certain Mr Newey is a recurring theme... *I might have missed some. Apologies if so. If you know better, please add your selection to the thread!

15. McLaren-Mercedes MP4-13 - Australian Grand Prix 1998

Qualifying margin: 0.757s

McLaren had poached star designer Adrian Newey from Williams during the 1997 season, and the MP4-13 was the first car created completely under his supervision. Radical changes to the regulations for 1998 saw the cars made narrower, and equipped with grooved tyres. Newey had a further complication to deal with in the form of a change of tyre supplier from Goodyear to Bridgestone. However, as so often in his career, he rose to the occasion superbly.

Drivers Mika Hakkinen and David Coulthard comfortably locked out the front row of the grid in Melbourne, with Michael Schumacher's Ferrari the best of the rest in third, three-quarters of a second adrift. Despite a phantom pitstop for Hakkinen in the race, the Woking team cruised to a 1-2 finish, and the Finn would go on to seal the championship from Schumacher at the final race of the season, after a strong Ferrari fightback.

14. Lotus-Renault 98T - Brazilian Grand Prix 1986

Qualifying margin: 0.765s

Arguably this one appears on the list more due to its driver than any greatness inherent to the car itself. Ayrton Senna joined Lotus in 1985, and for the next three seasons would provide a major headache to the frontrunning McLaren and Williams teams despite the considerable limitations of the Lotus chassis. The 98T, designed by Gerard Ducarouge and Martin Ogilvie, was the last Lotus until 2011 to benefit from a Renault engine, and the French manufacturer spent considerable time perfecting their EF15B V6 qualifying turbo, a unit producing well in excess of 1000bhp and with every component pushed to the limit on reliability in the quest for more power.

Senna took the pole at Rio's Jacarepagua circuit ahead of the home-town hero Nelson Piquet in his Williams, with the second Williams of Nigel Mansell lining up third. Piquet would go on to win the race from Senna, and the Williams drivers largely dominated the season, but thanks to mistakes, and to them taking points from each other, McLaren's Alain Prost snuck in to steal the title at the final round. Senna finished fourth in the Drivers' Championship with two wins, while team-mate Johnny Dumfries scored a further three points, leaving Lotus solidly third in the Constructors'.

13. Red Bull-Renault RB7 - Australian Grand Prix 2011

Qualifying margin: 0.778s

Another of Adrian Newey's creations shows stunning speed on its debut down under. Having built the fastest car of 2010, only to watch their drivers almost contrive to throw the titles away, Red Bull were favourites heading into the 2011 campaign. Regulation changes had the potential to mix things up, with the "double-diffuser" and "f-duct" innovations banned, while all the teams had to adapt to control tyres from new supplier Pirelli.

Typically, Red Bull did not show their hand in practice or the first part of qualifying, but when the RB7 was finally let off the leash, the pace it showed in the hands of Sebastian Vettel was simply stunning. The reigning world champion completely dominated the opposition, his closest rival Lewis Hamilton over three-quarters of a second behind in his McLaren. Vettel went on to secure the race win in relative comfort. Team-mate Mark Webber struggled from his third place grid position and finished fifth, mystified by his comparative lack of pace.

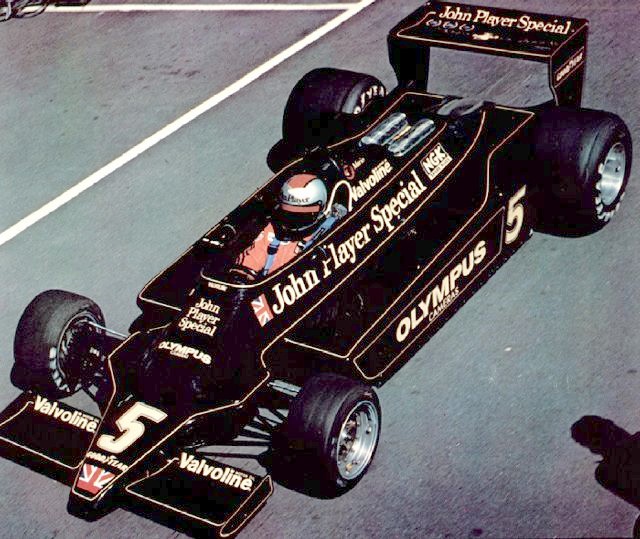

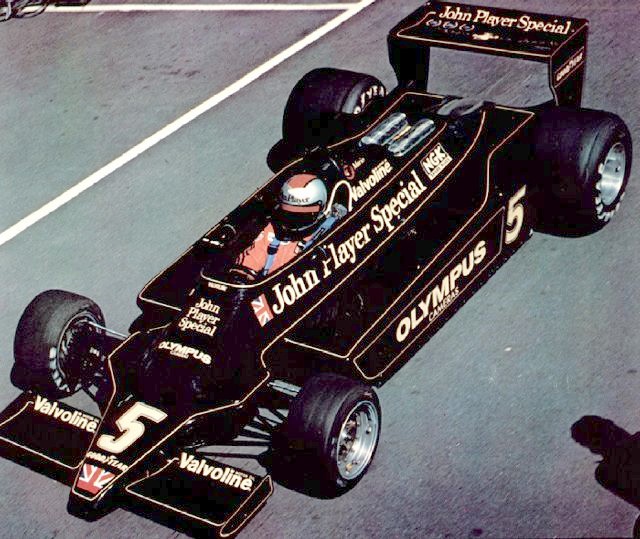

12. Lotus-Ford 79 - Belgian Grand Prix 1978

Qualifying margin: 0.790s

Lotus had struggled through the mid-1970s to produce a convincing replacement for their ageing Type 72. The Type 78 car, however, which debuted in 1977, proved a step forward. With the blessing of team founder Colin Chapman, the design team of Ralph Bellamy, Martin Ogilvie and Peter Wright worked on producing more downforce through a specially shaped underbody. Their work at the Imperial College windtunnel showed that a car equipped with venturi tunnels and low side skirts could produce many times the downforce of conventional cars. These lessons were explored on the Type 78, but the Type 79 would be the first car to fully integrate the concept, with alterations to the layout to ensure maximum airflow to the all-important underbody area.

The debut of the new car was delayed until the sixth race of the 1978 championship, and even at Zolder there was only one car ready for team leader Mario Andretti - team mate Ronnie Peterson persevered with the older Type 78. Mario - who described the car as 'painted to the road' - took the new 79 to a dominant pole position, over three quarters of a second faster than Carlos Reutemann's Ferrari. Peterson qualified seventh, but as Mario dominated on race day, moved through the field to complete a 1-2 finish for the team. Andretti would go on to take the championship later in the year at Monza, but the achievement was stung by tragedy, as Peterson was gravely injured in a first lap accident. Ronnie later succumbed to his injuries in hospital.

11. McLaren-Honda MP4-5 - Brazilian Grand Prix 1989

Qualifying margin: 0.870s

1988 was McLaren's greatest ever season, as drivers Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost won fifteen of the sixteen races in their Honda turbo-powered cars. For 1989, turbos were finally banned, and Honda supplied an all-new V10 engine for Neil Oatley's MP4-5 design. Rivals may have hoped that the change of engine would give them an opportunity to close the gap to the Woking team, and there was some encouragement in qualifying, as Prost could only qualify fifth. However, reigning champion Senna produced another of his devastating qualifying laps to secure pole position with a lap in 1:25.302, Williams' Riccardo Patrese the nearest challenger setting a time of 1:26.172.

On race day at Rio things went downhill fast for the team, however. Senna collided with Gerhard Berger's Ferrari at the start, damaging his front wing, while Prost could only climb as far as second place. It was Nigel Mansell who took an unexpected win on his Ferrari debut, the car's semi-automatic gearbox holding together despite all expectations - including those of the team and driver himself! McLaren would go on to win both championships in 1989, the drivers' crown being decided in a controversial collision at Suzuka in favour of Alain Prost, who promptly took his number one with him to Maranello as Berger's replacement.

10. Ferrari 625 - Argentine Grand Prix 1954

Qualifying margin: 0.900s

After two years of running the world championship to the underwhelming Formula Two regulations, 1954 saw the 'return to power', with engines uprated to 2.5 litres. Four manufacturers prepared new cars for the change in rules, though only two - Ferrari and Maserati - had their new models ready for the championship opener in Buenos Aires on January 17th. Ferrari's 625 was an evolution of their successful 500 F2 model, with the main change in the engine bay, and rival Maserati's 250F would prove to be the better machine overall.

In Argentina, however, it was first blood to Ferrari, as 1950 champion Giuseppe Farina took pole position, ahead of the local heroes Jose Froilan Gonzalez (Ferrari) and Juan Manuel Fangio, who was racing for Maserati while waiting for his Mercedes Grand Prix car to be completed. In the race, Mike Hawthorn moved up to make it a Ferrari 1-2-3 in the early stages, but a mid-race shower upset their chances and allowed Fangio to demonstrate his virtuosity, the Maserati driver mastering the conditions to take victory. Farina finished second after a pitstop for a helmet visor, while Gonzalez completed the podium having spun his car in the wet conditions.

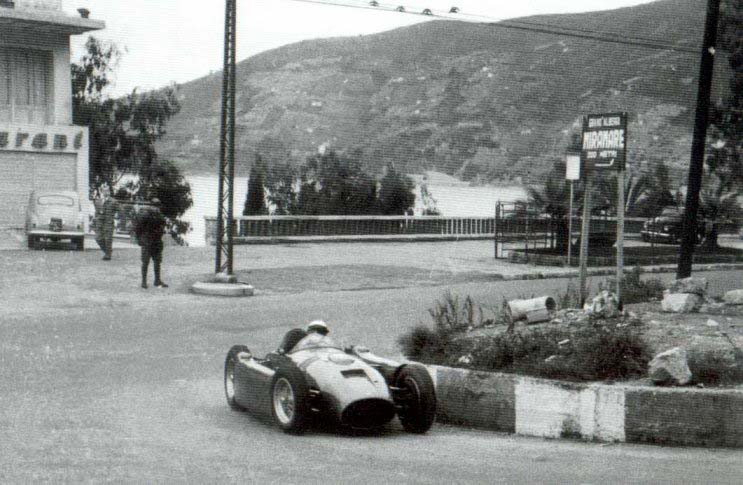

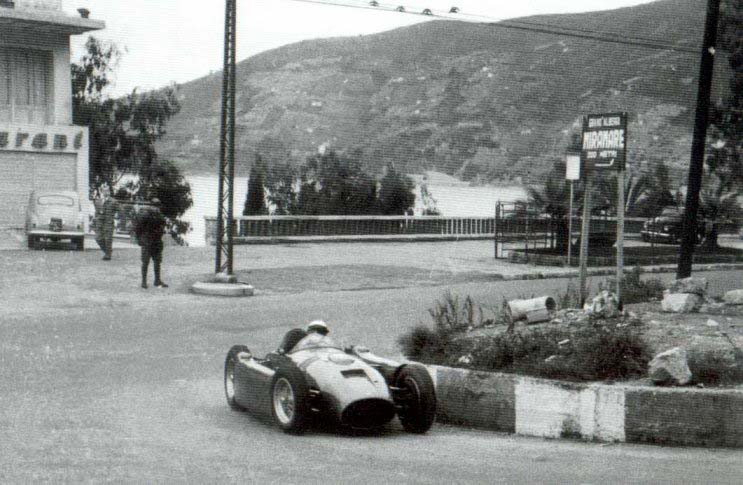

9. Lancia D50 - Spanish Grand Prix 1954

Qualifying margin: 1.000s

Alberto Ascari was the reigning double world champion from 1952-3, but for the rules changes in 1954 moved to Lancia. Their D50 car was repeatedly subject to delay, however, and ultimately only made its world championship debut at the final race of the season, the Spanish Grand Prix on the Pedralbes street circuit in Barcelona. Designer Vittorio Jano had produced an innovative car, which used the engine as a stressed member of the chassis, and employed signature pannier fuel tanks between the wheels, which improved streamlining and weight distribution.

Ascari showed the potential battle that might have been between Lancia and Mercedes when he took pole at Pedralbes, a second clear of Juan Manuel Fangio's W196, who had already secured the championship. A second car, for Italian veteran Luigi Villoresi, lined up fifth. Lancia's race would only last ten laps, however, Villoresi stopping with brake problems on the second lap, while Ascari was also forced to retire early with clutch failure. The D50 raced on into 1955, but was similarly plagued by mechanical unreliability, while the company suffered increasing financial difficulties. Following Ascari's death testing a Ferrari at Monza matters came to a head, and the assets of the racing team were transferred to Ferrari, who continued to race the D50 with their own evolutions on into 1957, Fangio taking the 1956 championship with the car now known as a 'Lancia-Ferrari'.

8. Mercedes-Benz W196 - French Grand Prix 1954

Qualifying margin: 1.100s

Today, when the slightest aerodynamic tweak can prompt an avalanche of internet speculation, it is hard to imagine the effect the arrival of the Mercedes W196 had on the postwar motor racing landscape. With full streamliner bodywork, the W196 represented an exceptional marriage of form and function, and rendered rivals' machinery obsolete overnight. The car employed technology new to Grand Prix racing, including desmodromic valve actuation and direct fuel injection. Even more impressive was the Stuttgart mechanics' attention to detail, resulting in a lighter but stiffer chassis than rival cars, and an unchallenged record of reliability.

Juan Manuel Fangio and Karl Kling duly dominated at the high-speed triangular road course outside Reims, finishing first and second in both qualifying and the race. Fangio went on to win three of the five remaining races, and his second world championship. For 1955 Stirling Moss was recruited, and success continued, with five further wins from six starts, including a landmark 1-2-3-4 finish at Aintree in the British Grand Prix. Fangio was champion again, but following the Le Mans disaster in June which claimed the lives of 83 spectators, Mercedes withdrew from motorsport and the W196 was retired.

7. McLaren-Honda MP4-6 - United States Grand Prix 1991

Qualifying margin: 1.121s

Going into the 1991 season, McLaren's momentum seemed unstoppable. The team had won three consecutive drivers' and constructors' championships, and Honda was producing a new V12 engine to replace the V10 used since 1989. More importantly, the team still had the peerless skills of Ayrton Senna to call upon. Neil Oatley had designed the MP4-6 as a sensible evolution of the MP4-5B, but the car's production was badly delayed. The assembly of the race cars was only completed in the garage at Phoenix, and first turned their wheels in anger in Friday practice.

Once underway, though, the speed of the car was in no doubt, and Senna was in devastating form around the narrow streets of Phoenix, taking pole position by a full second from nemesis Alain Prost in the Ferrari 642. Gerhard Berger qualified the second McLaren seventh. In the race the story was repeated, Senna building a 30-second lead seemingly without effort, Prost trailing in a distant second. It was the first of four consecutive wins for Senna to kick off his title defence, but rapid development of the rival Williams from mid-season looked like it might give Riccardo Patrese or Nigel Mansell an opportunity to challenge the Brazilian. In the event, Williams' advanced gearbox proved too fragile, and Senna took his third and final Formula One crown.

6. Ligier-Ford JS11 - Argentine Grand Prix 1979

Qualifying margin: 1.140s

Lotus' ground effects Type 79 rewrote the design rulebook in 1978, and rival designers were struggling to first understand, and then to implement, the principles on their own cars. Aerodynamics were not as well understood as today, and development was often a case of trial-and-error, with windtunnel testing limited only to the top teams, and then usually only for a few days per month. Ligier had not previously been one of the front-running teams, but designer Gerard Ducarouge produced an effective ground effects car in the JS11, powered by the Cosworth DFV V8 engine.

To the surprise of everybody (including themselves), Ligier found themselves at the head of the field throughout the opening Argentine Grand Prix weekend. The cars of Jacques Laffite and Patrick Depailler secured the front row of the grid by over a second from Carlos Reutemann's Lotus 79. Depailler led from the start, but Laffite took over before half-distance and cruising home for the victory. A late pitstop left Depailler down in fourth, but at the next race in Brazil the team were this time able to convert a 1-2 in qualifying into a similar race result.

Legend has it that Ligier scarcely understood why their car worked as well as it did, and as the season went on and rival teams introduced new cars, their performances faded. It has even been suggested that the car setups had been written on the back of a cigarette packet, which had subsequently been lost! Whatever the truth, Laffite took a further four podiums through the season and finished fourth in the drivers' championship, while the team took third in the constructors', their best-ever result.

5. McLaren-Mercedes MP4-14 - Australian Grand Prix 1999

Qualifying margin: 1.319s

It was very much a case of deja vu at Melbourne in 1999, as the latest Adrian Newey-designed McLaren was unveiled and proceeded to blow the opposition away on sheer speed. The MP4-14 was derived from the previous season's championship-winning car, and drivers Mika Hakkinen and David Coulthard were retained to drive it. With the withdrawal of Goodyear, Bridgestone now supplied the entire field, and McLaren's greater experience of the tyre compared with their main rivals Ferrari was to prove a key part of their success, even if an extra groove had been added to the front tyres.

In qualifying Hakkinen was rampant, faster than Coulthard by almost half a second and 1.3 seconds ahead of Michael Schumacher's Ferrari in third. The race, however, was a break from the script written in 1998, as both cars suffered from reliability gremlins - Coulthard dropping out of second after 13 laps with hydraulic issues, while Hakkinen's car failed to pick up speed after a Safety Car period and retired on lap 22, leaving Eddie Irvine to take his first Grand Prix win. Hakkinen would go on to take a back-to-back championship after a season-long battle with first Schumacher, then after the German's leg-breaking accident at Silverstone, Irvine in the other Ferrari. The inconsistent reliability record, and some errors from the drivers allowed Ferrari to snatch the constructors' championship.

4. Alfa Romeo 158 - British Grand Prix 1950

Qualifying margin: 1.800s

First, a disclaimer - the 'Alfetta' did not make its debut at the first ever world championship race at Silverstone in 1950. The car was already twelve years old, having been designed for the pre-war secondary 'Voiturette' class. It was designed by Gioacchino Colombo, and featured a 1.5 litre supercharged engine, with a power output of 350bhp. With the advent of Formula One regulations in the early post-war years, Alfa Romeo dusted off their 158s and went into battle armed with the 'Three Fs' - Juan Manuel Fangio, Giuseppe Farina and Luigi Fagioli. Their main rivals were to be Scuderia Ferrari, Enzo having formerly run the Alfa racing team but now striking out on his own.

Sadly for the crowd of over 100,000 at Silverstone, however, the Ferraris did not make the trip to England, and consequently the race was an Alfa benefit. A fourth car had been entered for England's premier driver of the time, Reg Parnell, and he completed a 1-2-3-4 for the Alfas in qualifying. Prince Bira's privately-entered Maserati was the best of the rest on the 4-3-4 grid, ahead of the unsupercharged 4.5 litre Talbots. In the race the Alfas put on a show for the spectators but faced no opposition, Farina winning from Fagioli and Parnell, Fangio having dropped out with engine failure. Farina and Fangio between them would split the wins in all six Grands Prix held in 1950, the Italian taking the world championship due to a fourth place at Spa.

The 158s were progressively evolved and raced on into 1951 in 159 form, with power output increasing to a peak of 425bhp by the end of that season. This took a heavy toll on fuel consumption, however, the thirsty Alfas requiring more pitstops than their rivals, and also compromised reliability, the transmission and brakes needing to be beefed up to cope with the increased demands placed upon them. Fangio took his first world title after a close battle with Alberto Ascari's ever-improving Ferrari, but Alfa withdrew at the end of the season, prompting the move to Formula 2 regulations for 1952.

3. Williams-Renault FW19 - Australian Grand Prix 1997

Qualifying margin: 2.103s

The Williams Renault steamroller was coming to the end of the road in 1997. Adrian Newey had been poached by rivals McLaren, and would not be on the Williams pitwall in Melbourne. The French engine supplier would withdraw from F1 as a works entity at the end of the year, while Goodyear's monopoly over tyre supply was being challenged for the first time in six years by Bridgestone. Newey's last Williams was one of his best, however, and against rivals in various forms of rebuilding and disarray, it was able to achieve some startling performance differentials. World champion Damon Hill had been replaced by Heinz-Harald Frentzen, Jacques Villeneuve staying on board for his second season in F1.

Villeneuve annihilated the opposition in qualifying for the first race of the season, outpacing Frentzen by over a second-and-a-half, and establishing a gap to the lead Ferrari of Michael Schumacher of over two seconds. Ferrari were unhappy with the handling of their car, and David Coulthard's McLaren split the two Italian cars on the grid. At the first corner, however, it all came to nothing for Jacques, as his FW19 was hit from behind by Irvine's Ferrari and retired from the event. Frentzen continued in the lead, but his brakes faded and finally failed at the first corner late in the race, gifting Coulthard McLaren's first win for over three years.

Over the course of the season Ferrari improved their F310B and Schumacher was able to mount a championship challenge, helped in part by some inconsistent performances from the Williams drivers, and tactical blunders by the team. At the season finale at Jerez Schumacher unsuccessfully tried to take out Villeneuve, the Canadian continuing in a damaged car to take the points he needed to become world champion - Williams' last to date.

2. Williams-Honda FW11B - Brazilian Grand Prix 1987

Qualifying margin: 2.280s

In the FW11, Williams had built the fastest car of the 1986 season, its turbocharged Honda V6 proving to be by far the most effective engine in the field, but it had been a tough year for the team, with team founder Frank Williams' near-fatal car crash and internal strife between drivers Nigel Mansell and Nelson Piquet. Despite a considerable car disadvantage, McLaren's Alain Prost was able to stay on terms with the Williams pair in the championship, and take the title following Mansell's dramatic blow-out in Adelaide. The governing body placed new restrictions on the Honda turbo for the 1987 season, but designers Patrick Head and Frank Dernie reasoned that the basically well-engineered car did not require drastic changes, and so for 1987 a revised FW11B was to lead the team's challenge.

The new car proved to be more than up to the task in qualifying at Rio, Mansell scorching to pole position in a time of 1:26.128, home town man Piquet following up some four tenths of a second adrift. Ayrton Senna, whose Lotus was now equipped with the same Honda engine as the Williams, found himself third despite only setting a fastest time of 1:28.408, over two seconds away from Mansell. The McLaren MP4-3 of defending champion Prost lined up fifth, and over three seconds in arrears.

Things unravelled for Williams in the race, however, Mansell making a poor getaway from the lights and dropping to fifth. Things went from bad to worse shortly afterwards, rising engine temperatures resulting in both cars having to pit to have debris removed from their radiators. The pair began the long climb back through the field as Prost established himself in the lead ahead of Senna. Piquet could only make it up as far as second by the chequered flag, while a late puncture consigned Mansell to sixth.

The season proved to be one of Williams domination, Prost's McLaren and Senna's Lotus too uncompetitive to allow them to challenge. Mansell generally had the edge, but fortune favoured Piquet, and arriving at Suzuka for the penultimate race it was the Brazilian with the points lead. A big accident for Mansell in practice left him unable to complete the season, and so Piquet secured his third and last world championship before the race had even begun.

1. Ferrari 500 - Swiss Grand Prix 1952

Qualifying margin: 4.600s

With Alfa Romeo's withdrawal from Grand Prix racing at the end of 1951, the infant world championship looked in danger of collapse. Only two factory teams, Ferrari and BRM, were in a position to field Formula One machinery in 1952, and BRM's V16 had shown ghastly reliability at the few events at which it had appeared. A Ferrari steamroller was unlikely to attract big crowds to the races, and organisers began to pressure the governing body, the CSI, into action. Formula 2 had been established in 1948 as a supporting category, with smaller, lighter 2-litre cars, and many more manufacturers had built cars to these rules. Eventually the CSI decided to grant Formula 2 world championship status, and so although Formula 1 races continued to be held, they did not count for points.

If the CSI had hoped to prevent Ferrari dominating, however, they were utterly mistaken. Maserati had hired world champion Fangio to drive their new car, but he was injured before the season started and had to sit out the 1952 season. Ferrari's new 500, a simple solid design powered by an inline-4 engine, proved unstoppable. Their lead driver, Alberto Ascari, missed the Swiss event as he was in the USA, qualifying for the Indianapolis 500 - then a points-scoring round of the championship. In his absence, veteran Piero Taruffi led the red tide in qualifying, the men from Maranello taking first, second, fourth and fifth on the grid; the French Gordini of Robert Manzon the only interloper.

Second-placed qualifier Giuseppe Farina took the lead at the start, but dropped out early with mechanical failure, leaving the way clear for Taruffi to sweep to his only Grand Prix victory. Rudi Fischer finished a distant second in another 500, with Jean Behra's Gordini a lapped third at the end of the three hours. The remainder of the season proved Ferrari's superiority - though his challenge at Indy faltered, Ascari won all six of the subsequent rounds of the championship, with five pole positions (Farina scoring the other, at Silverstone).

Into 1953, despite the return of Fangio, Ascari continued to dominate, taking the first three races of the season, his nine wins in a row remaining an all-time record. Ferrari were only finally toppled at the final event of the season at Monza, Fangio's Maserati winning after Ascari collided with another car. For 1954 the rules were changed again, bringing down the curtain on the 500. The car won thirteen of the fourteen races for which it was entered, ten with Ascari at the wheel, and took twelve pole positions.

There follows a run-down of the best 15 performances* by brand new cars since the F1 world championship began in 1950. A certain Mr Newey is a recurring theme... *I might have missed some. Apologies if so. If you know better, please add your selection to the thread!

15. McLaren-Mercedes MP4-13 - Australian Grand Prix 1998

Qualifying margin: 0.757s

McLaren had poached star designer Adrian Newey from Williams during the 1997 season, and the MP4-13 was the first car created completely under his supervision. Radical changes to the regulations for 1998 saw the cars made narrower, and equipped with grooved tyres. Newey had a further complication to deal with in the form of a change of tyre supplier from Goodyear to Bridgestone. However, as so often in his career, he rose to the occasion superbly.

Drivers Mika Hakkinen and David Coulthard comfortably locked out the front row of the grid in Melbourne, with Michael Schumacher's Ferrari the best of the rest in third, three-quarters of a second adrift. Despite a phantom pitstop for Hakkinen in the race, the Woking team cruised to a 1-2 finish, and the Finn would go on to seal the championship from Schumacher at the final race of the season, after a strong Ferrari fightback.

14. Lotus-Renault 98T - Brazilian Grand Prix 1986

Qualifying margin: 0.765s

Arguably this one appears on the list more due to its driver than any greatness inherent to the car itself. Ayrton Senna joined Lotus in 1985, and for the next three seasons would provide a major headache to the frontrunning McLaren and Williams teams despite the considerable limitations of the Lotus chassis. The 98T, designed by Gerard Ducarouge and Martin Ogilvie, was the last Lotus until 2011 to benefit from a Renault engine, and the French manufacturer spent considerable time perfecting their EF15B V6 qualifying turbo, a unit producing well in excess of 1000bhp and with every component pushed to the limit on reliability in the quest for more power.

Senna took the pole at Rio's Jacarepagua circuit ahead of the home-town hero Nelson Piquet in his Williams, with the second Williams of Nigel Mansell lining up third. Piquet would go on to win the race from Senna, and the Williams drivers largely dominated the season, but thanks to mistakes, and to them taking points from each other, McLaren's Alain Prost snuck in to steal the title at the final round. Senna finished fourth in the Drivers' Championship with two wins, while team-mate Johnny Dumfries scored a further three points, leaving Lotus solidly third in the Constructors'.

13. Red Bull-Renault RB7 - Australian Grand Prix 2011

Qualifying margin: 0.778s

Another of Adrian Newey's creations shows stunning speed on its debut down under. Having built the fastest car of 2010, only to watch their drivers almost contrive to throw the titles away, Red Bull were favourites heading into the 2011 campaign. Regulation changes had the potential to mix things up, with the "double-diffuser" and "f-duct" innovations banned, while all the teams had to adapt to control tyres from new supplier Pirelli.

Typically, Red Bull did not show their hand in practice or the first part of qualifying, but when the RB7 was finally let off the leash, the pace it showed in the hands of Sebastian Vettel was simply stunning. The reigning world champion completely dominated the opposition, his closest rival Lewis Hamilton over three-quarters of a second behind in his McLaren. Vettel went on to secure the race win in relative comfort. Team-mate Mark Webber struggled from his third place grid position and finished fifth, mystified by his comparative lack of pace.

12. Lotus-Ford 79 - Belgian Grand Prix 1978

Qualifying margin: 0.790s

Lotus had struggled through the mid-1970s to produce a convincing replacement for their ageing Type 72. The Type 78 car, however, which debuted in 1977, proved a step forward. With the blessing of team founder Colin Chapman, the design team of Ralph Bellamy, Martin Ogilvie and Peter Wright worked on producing more downforce through a specially shaped underbody. Their work at the Imperial College windtunnel showed that a car equipped with venturi tunnels and low side skirts could produce many times the downforce of conventional cars. These lessons were explored on the Type 78, but the Type 79 would be the first car to fully integrate the concept, with alterations to the layout to ensure maximum airflow to the all-important underbody area.

The debut of the new car was delayed until the sixth race of the 1978 championship, and even at Zolder there was only one car ready for team leader Mario Andretti - team mate Ronnie Peterson persevered with the older Type 78. Mario - who described the car as 'painted to the road' - took the new 79 to a dominant pole position, over three quarters of a second faster than Carlos Reutemann's Ferrari. Peterson qualified seventh, but as Mario dominated on race day, moved through the field to complete a 1-2 finish for the team. Andretti would go on to take the championship later in the year at Monza, but the achievement was stung by tragedy, as Peterson was gravely injured in a first lap accident. Ronnie later succumbed to his injuries in hospital.

11. McLaren-Honda MP4-5 - Brazilian Grand Prix 1989

Qualifying margin: 0.870s

1988 was McLaren's greatest ever season, as drivers Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost won fifteen of the sixteen races in their Honda turbo-powered cars. For 1989, turbos were finally banned, and Honda supplied an all-new V10 engine for Neil Oatley's MP4-5 design. Rivals may have hoped that the change of engine would give them an opportunity to close the gap to the Woking team, and there was some encouragement in qualifying, as Prost could only qualify fifth. However, reigning champion Senna produced another of his devastating qualifying laps to secure pole position with a lap in 1:25.302, Williams' Riccardo Patrese the nearest challenger setting a time of 1:26.172.

On race day at Rio things went downhill fast for the team, however. Senna collided with Gerhard Berger's Ferrari at the start, damaging his front wing, while Prost could only climb as far as second place. It was Nigel Mansell who took an unexpected win on his Ferrari debut, the car's semi-automatic gearbox holding together despite all expectations - including those of the team and driver himself! McLaren would go on to win both championships in 1989, the drivers' crown being decided in a controversial collision at Suzuka in favour of Alain Prost, who promptly took his number one with him to Maranello as Berger's replacement.

10. Ferrari 625 - Argentine Grand Prix 1954

Qualifying margin: 0.900s

After two years of running the world championship to the underwhelming Formula Two regulations, 1954 saw the 'return to power', with engines uprated to 2.5 litres. Four manufacturers prepared new cars for the change in rules, though only two - Ferrari and Maserati - had their new models ready for the championship opener in Buenos Aires on January 17th. Ferrari's 625 was an evolution of their successful 500 F2 model, with the main change in the engine bay, and rival Maserati's 250F would prove to be the better machine overall.

In Argentina, however, it was first blood to Ferrari, as 1950 champion Giuseppe Farina took pole position, ahead of the local heroes Jose Froilan Gonzalez (Ferrari) and Juan Manuel Fangio, who was racing for Maserati while waiting for his Mercedes Grand Prix car to be completed. In the race, Mike Hawthorn moved up to make it a Ferrari 1-2-3 in the early stages, but a mid-race shower upset their chances and allowed Fangio to demonstrate his virtuosity, the Maserati driver mastering the conditions to take victory. Farina finished second after a pitstop for a helmet visor, while Gonzalez completed the podium having spun his car in the wet conditions.

9. Lancia D50 - Spanish Grand Prix 1954

Qualifying margin: 1.000s

Alberto Ascari was the reigning double world champion from 1952-3, but for the rules changes in 1954 moved to Lancia. Their D50 car was repeatedly subject to delay, however, and ultimately only made its world championship debut at the final race of the season, the Spanish Grand Prix on the Pedralbes street circuit in Barcelona. Designer Vittorio Jano had produced an innovative car, which used the engine as a stressed member of the chassis, and employed signature pannier fuel tanks between the wheels, which improved streamlining and weight distribution.

Ascari showed the potential battle that might have been between Lancia and Mercedes when he took pole at Pedralbes, a second clear of Juan Manuel Fangio's W196, who had already secured the championship. A second car, for Italian veteran Luigi Villoresi, lined up fifth. Lancia's race would only last ten laps, however, Villoresi stopping with brake problems on the second lap, while Ascari was also forced to retire early with clutch failure. The D50 raced on into 1955, but was similarly plagued by mechanical unreliability, while the company suffered increasing financial difficulties. Following Ascari's death testing a Ferrari at Monza matters came to a head, and the assets of the racing team were transferred to Ferrari, who continued to race the D50 with their own evolutions on into 1957, Fangio taking the 1956 championship with the car now known as a 'Lancia-Ferrari'.

8. Mercedes-Benz W196 - French Grand Prix 1954

Qualifying margin: 1.100s

Today, when the slightest aerodynamic tweak can prompt an avalanche of internet speculation, it is hard to imagine the effect the arrival of the Mercedes W196 had on the postwar motor racing landscape. With full streamliner bodywork, the W196 represented an exceptional marriage of form and function, and rendered rivals' machinery obsolete overnight. The car employed technology new to Grand Prix racing, including desmodromic valve actuation and direct fuel injection. Even more impressive was the Stuttgart mechanics' attention to detail, resulting in a lighter but stiffer chassis than rival cars, and an unchallenged record of reliability.

Juan Manuel Fangio and Karl Kling duly dominated at the high-speed triangular road course outside Reims, finishing first and second in both qualifying and the race. Fangio went on to win three of the five remaining races, and his second world championship. For 1955 Stirling Moss was recruited, and success continued, with five further wins from six starts, including a landmark 1-2-3-4 finish at Aintree in the British Grand Prix. Fangio was champion again, but following the Le Mans disaster in June which claimed the lives of 83 spectators, Mercedes withdrew from motorsport and the W196 was retired.

7. McLaren-Honda MP4-6 - United States Grand Prix 1991

Qualifying margin: 1.121s

Going into the 1991 season, McLaren's momentum seemed unstoppable. The team had won three consecutive drivers' and constructors' championships, and Honda was producing a new V12 engine to replace the V10 used since 1989. More importantly, the team still had the peerless skills of Ayrton Senna to call upon. Neil Oatley had designed the MP4-6 as a sensible evolution of the MP4-5B, but the car's production was badly delayed. The assembly of the race cars was only completed in the garage at Phoenix, and first turned their wheels in anger in Friday practice.

Once underway, though, the speed of the car was in no doubt, and Senna was in devastating form around the narrow streets of Phoenix, taking pole position by a full second from nemesis Alain Prost in the Ferrari 642. Gerhard Berger qualified the second McLaren seventh. In the race the story was repeated, Senna building a 30-second lead seemingly without effort, Prost trailing in a distant second. It was the first of four consecutive wins for Senna to kick off his title defence, but rapid development of the rival Williams from mid-season looked like it might give Riccardo Patrese or Nigel Mansell an opportunity to challenge the Brazilian. In the event, Williams' advanced gearbox proved too fragile, and Senna took his third and final Formula One crown.

6. Ligier-Ford JS11 - Argentine Grand Prix 1979

Qualifying margin: 1.140s

Lotus' ground effects Type 79 rewrote the design rulebook in 1978, and rival designers were struggling to first understand, and then to implement, the principles on their own cars. Aerodynamics were not as well understood as today, and development was often a case of trial-and-error, with windtunnel testing limited only to the top teams, and then usually only for a few days per month. Ligier had not previously been one of the front-running teams, but designer Gerard Ducarouge produced an effective ground effects car in the JS11, powered by the Cosworth DFV V8 engine.

To the surprise of everybody (including themselves), Ligier found themselves at the head of the field throughout the opening Argentine Grand Prix weekend. The cars of Jacques Laffite and Patrick Depailler secured the front row of the grid by over a second from Carlos Reutemann's Lotus 79. Depailler led from the start, but Laffite took over before half-distance and cruising home for the victory. A late pitstop left Depailler down in fourth, but at the next race in Brazil the team were this time able to convert a 1-2 in qualifying into a similar race result.

Legend has it that Ligier scarcely understood why their car worked as well as it did, and as the season went on and rival teams introduced new cars, their performances faded. It has even been suggested that the car setups had been written on the back of a cigarette packet, which had subsequently been lost! Whatever the truth, Laffite took a further four podiums through the season and finished fourth in the drivers' championship, while the team took third in the constructors', their best-ever result.

5. McLaren-Mercedes MP4-14 - Australian Grand Prix 1999

Qualifying margin: 1.319s

It was very much a case of deja vu at Melbourne in 1999, as the latest Adrian Newey-designed McLaren was unveiled and proceeded to blow the opposition away on sheer speed. The MP4-14 was derived from the previous season's championship-winning car, and drivers Mika Hakkinen and David Coulthard were retained to drive it. With the withdrawal of Goodyear, Bridgestone now supplied the entire field, and McLaren's greater experience of the tyre compared with their main rivals Ferrari was to prove a key part of their success, even if an extra groove had been added to the front tyres.

In qualifying Hakkinen was rampant, faster than Coulthard by almost half a second and 1.3 seconds ahead of Michael Schumacher's Ferrari in third. The race, however, was a break from the script written in 1998, as both cars suffered from reliability gremlins - Coulthard dropping out of second after 13 laps with hydraulic issues, while Hakkinen's car failed to pick up speed after a Safety Car period and retired on lap 22, leaving Eddie Irvine to take his first Grand Prix win. Hakkinen would go on to take a back-to-back championship after a season-long battle with first Schumacher, then after the German's leg-breaking accident at Silverstone, Irvine in the other Ferrari. The inconsistent reliability record, and some errors from the drivers allowed Ferrari to snatch the constructors' championship.

4. Alfa Romeo 158 - British Grand Prix 1950

Qualifying margin: 1.800s

First, a disclaimer - the 'Alfetta' did not make its debut at the first ever world championship race at Silverstone in 1950. The car was already twelve years old, having been designed for the pre-war secondary 'Voiturette' class. It was designed by Gioacchino Colombo, and featured a 1.5 litre supercharged engine, with a power output of 350bhp. With the advent of Formula One regulations in the early post-war years, Alfa Romeo dusted off their 158s and went into battle armed with the 'Three Fs' - Juan Manuel Fangio, Giuseppe Farina and Luigi Fagioli. Their main rivals were to be Scuderia Ferrari, Enzo having formerly run the Alfa racing team but now striking out on his own.

Sadly for the crowd of over 100,000 at Silverstone, however, the Ferraris did not make the trip to England, and consequently the race was an Alfa benefit. A fourth car had been entered for England's premier driver of the time, Reg Parnell, and he completed a 1-2-3-4 for the Alfas in qualifying. Prince Bira's privately-entered Maserati was the best of the rest on the 4-3-4 grid, ahead of the unsupercharged 4.5 litre Talbots. In the race the Alfas put on a show for the spectators but faced no opposition, Farina winning from Fagioli and Parnell, Fangio having dropped out with engine failure. Farina and Fangio between them would split the wins in all six Grands Prix held in 1950, the Italian taking the world championship due to a fourth place at Spa.

The 158s were progressively evolved and raced on into 1951 in 159 form, with power output increasing to a peak of 425bhp by the end of that season. This took a heavy toll on fuel consumption, however, the thirsty Alfas requiring more pitstops than their rivals, and also compromised reliability, the transmission and brakes needing to be beefed up to cope with the increased demands placed upon them. Fangio took his first world title after a close battle with Alberto Ascari's ever-improving Ferrari, but Alfa withdrew at the end of the season, prompting the move to Formula 2 regulations for 1952.

3. Williams-Renault FW19 - Australian Grand Prix 1997

Qualifying margin: 2.103s

The Williams Renault steamroller was coming to the end of the road in 1997. Adrian Newey had been poached by rivals McLaren, and would not be on the Williams pitwall in Melbourne. The French engine supplier would withdraw from F1 as a works entity at the end of the year, while Goodyear's monopoly over tyre supply was being challenged for the first time in six years by Bridgestone. Newey's last Williams was one of his best, however, and against rivals in various forms of rebuilding and disarray, it was able to achieve some startling performance differentials. World champion Damon Hill had been replaced by Heinz-Harald Frentzen, Jacques Villeneuve staying on board for his second season in F1.

Villeneuve annihilated the opposition in qualifying for the first race of the season, outpacing Frentzen by over a second-and-a-half, and establishing a gap to the lead Ferrari of Michael Schumacher of over two seconds. Ferrari were unhappy with the handling of their car, and David Coulthard's McLaren split the two Italian cars on the grid. At the first corner, however, it all came to nothing for Jacques, as his FW19 was hit from behind by Irvine's Ferrari and retired from the event. Frentzen continued in the lead, but his brakes faded and finally failed at the first corner late in the race, gifting Coulthard McLaren's first win for over three years.

Over the course of the season Ferrari improved their F310B and Schumacher was able to mount a championship challenge, helped in part by some inconsistent performances from the Williams drivers, and tactical blunders by the team. At the season finale at Jerez Schumacher unsuccessfully tried to take out Villeneuve, the Canadian continuing in a damaged car to take the points he needed to become world champion - Williams' last to date.

2. Williams-Honda FW11B - Brazilian Grand Prix 1987

Qualifying margin: 2.280s

In the FW11, Williams had built the fastest car of the 1986 season, its turbocharged Honda V6 proving to be by far the most effective engine in the field, but it had been a tough year for the team, with team founder Frank Williams' near-fatal car crash and internal strife between drivers Nigel Mansell and Nelson Piquet. Despite a considerable car disadvantage, McLaren's Alain Prost was able to stay on terms with the Williams pair in the championship, and take the title following Mansell's dramatic blow-out in Adelaide. The governing body placed new restrictions on the Honda turbo for the 1987 season, but designers Patrick Head and Frank Dernie reasoned that the basically well-engineered car did not require drastic changes, and so for 1987 a revised FW11B was to lead the team's challenge.

The new car proved to be more than up to the task in qualifying at Rio, Mansell scorching to pole position in a time of 1:26.128, home town man Piquet following up some four tenths of a second adrift. Ayrton Senna, whose Lotus was now equipped with the same Honda engine as the Williams, found himself third despite only setting a fastest time of 1:28.408, over two seconds away from Mansell. The McLaren MP4-3 of defending champion Prost lined up fifth, and over three seconds in arrears.

Things unravelled for Williams in the race, however, Mansell making a poor getaway from the lights and dropping to fifth. Things went from bad to worse shortly afterwards, rising engine temperatures resulting in both cars having to pit to have debris removed from their radiators. The pair began the long climb back through the field as Prost established himself in the lead ahead of Senna. Piquet could only make it up as far as second by the chequered flag, while a late puncture consigned Mansell to sixth.

The season proved to be one of Williams domination, Prost's McLaren and Senna's Lotus too uncompetitive to allow them to challenge. Mansell generally had the edge, but fortune favoured Piquet, and arriving at Suzuka for the penultimate race it was the Brazilian with the points lead. A big accident for Mansell in practice left him unable to complete the season, and so Piquet secured his third and last world championship before the race had even begun.

1. Ferrari 500 - Swiss Grand Prix 1952

Qualifying margin: 4.600s

With Alfa Romeo's withdrawal from Grand Prix racing at the end of 1951, the infant world championship looked in danger of collapse. Only two factory teams, Ferrari and BRM, were in a position to field Formula One machinery in 1952, and BRM's V16 had shown ghastly reliability at the few events at which it had appeared. A Ferrari steamroller was unlikely to attract big crowds to the races, and organisers began to pressure the governing body, the CSI, into action. Formula 2 had been established in 1948 as a supporting category, with smaller, lighter 2-litre cars, and many more manufacturers had built cars to these rules. Eventually the CSI decided to grant Formula 2 world championship status, and so although Formula 1 races continued to be held, they did not count for points.

If the CSI had hoped to prevent Ferrari dominating, however, they were utterly mistaken. Maserati had hired world champion Fangio to drive their new car, but he was injured before the season started and had to sit out the 1952 season. Ferrari's new 500, a simple solid design powered by an inline-4 engine, proved unstoppable. Their lead driver, Alberto Ascari, missed the Swiss event as he was in the USA, qualifying for the Indianapolis 500 - then a points-scoring round of the championship. In his absence, veteran Piero Taruffi led the red tide in qualifying, the men from Maranello taking first, second, fourth and fifth on the grid; the French Gordini of Robert Manzon the only interloper.

Second-placed qualifier Giuseppe Farina took the lead at the start, but dropped out early with mechanical failure, leaving the way clear for Taruffi to sweep to his only Grand Prix victory. Rudi Fischer finished a distant second in another 500, with Jean Behra's Gordini a lapped third at the end of the three hours. The remainder of the season proved Ferrari's superiority - though his challenge at Indy faltered, Ascari won all six of the subsequent rounds of the championship, with five pole positions (Farina scoring the other, at Silverstone).

Into 1953, despite the return of Fangio, Ascari continued to dominate, taking the first three races of the season, his nine wins in a row remaining an all-time record. Ferrari were only finally toppled at the final event of the season at Monza, Fangio's Maserati winning after Ascari collided with another car. For 1954 the rules were changed again, bringing down the curtain on the 500. The car won thirteen of the fourteen races for which it was entered, ten with Ascari at the wheel, and took twelve pole positions.